Blog

Legacy Weeping Hemlock Taken Out by Snowstorm

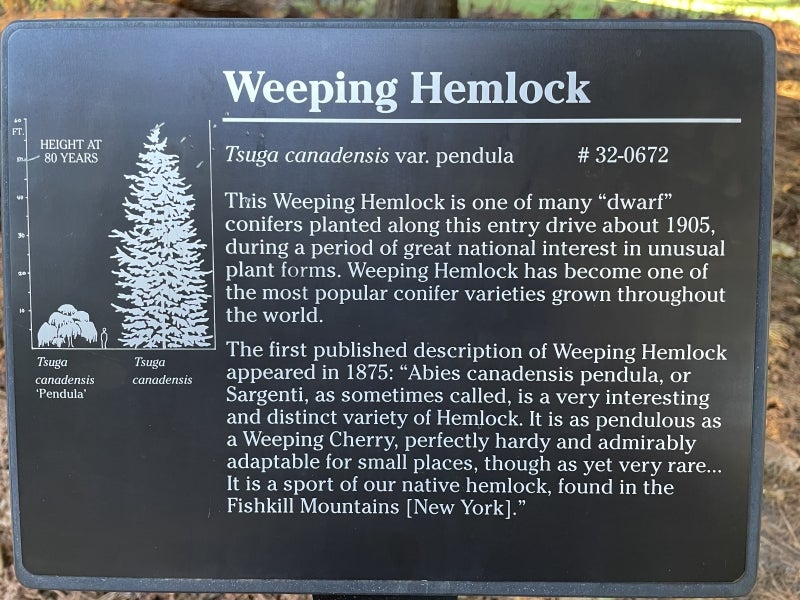

This past winter at the Morris Arboretum & Gardens was not very “wintery” by most accounts. Yes, there was some cold and a few snowstorms, but it was relatively un-winterlike. However, this was a winter of some discontent. In particular, the biggest discontent was the snowstorm of February 13. This quick-moving storm brought with it about 5 inches of wet snow, but it also brought down the venerable old weeping hemlock (Tsuga canadensis f. pendula) near the Swan Pond.

This was a legacy tree from the Morris era, most likely purchased by John from Parson & Sons Co. nursery in Flushing, New York. It grew at the Swan Pond almost since the Arboretum’s inception, until that fateful day in February. This tree was remarkable not only for its size and prominence but also because of the unique history it represented.

ONCE ABUNDANT

Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) was once a mainstay of the woodland flora throughout Pennsylvania. These long-lived, majestic conifers thrived across the state and were a significant component of William Penn’s wooded domain. In fact, hemlock trees were such an integral part of the flora throughout Pennsylvania that it was named the official state tree in 1931. Eastern hemlocks thrive in cool moist environments and often grow in dense shade on north facing slopes. They can grow slowly in adverse conditions, or rapidly in the right environment. Historically, this species was abundant in the Wissahickon gorge in cool ravines.

The story of our weeping hemlock does not start in Pennsylvania, but along the Lower Hudson River Valley in New York. It was here near the estate of General Joseph Howland that our story begins. Joseph Howland was a well-heeled member of society. His 4th-great-grandfather, John Howland, sailed to America as an indentured servant on the Mayflower and was an original signer of the Mayflower Compact creating the colony of Massachusetts. Despite arriving in America in bondage, the Howland family grew to prominence as merchants and businesspeople. By the 1830s, the shipping firm of Howland & Aspinwall became a leading importer of porcelain, silk, and tea from China. Thus it was, in 1834, that Joseph Howland was born into a family of wealth and prominence.

Joseph Howland was home-schooled, a man of firm convictions, an astute business leader, deeply religious, and a staunch anti-slavery activist. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted in the 16th New York Infantry Regiment and marched off to war. He distinguished himself in early combat and rose to the rank of colonel. He was seriously wounded at the First Battle of Bull Run and his injuries forced him into retirement. He was promoted to brigadier general upon leaving the Army, and he proudly wore this rank for the remainder of his life.

General Howland returned to his Beacon, New York, estate for his recovery. An active man, he often ventured out to explore the forests near his estate. It was on one of his convalescent forays near Fishkill Mountain that he discovered an unusual hemlock showing “a decidedly weeping form.” The tree grew in dense shade and hugged the ground in a large mound. He found several seedlings around this tree that also exhibited this same weeping characteristic. He collected four of these seedlings and planted one on his grounds. He gave one to his neighbor Henry Winthrop Sargent. Henry Sargent was an avid conifer collector and planted it in his own garden in Beacon. One of the other seedlings went to Henry’s cousin, Professor Charles S. Sargent, director of the Arnold Arboretum. Charles Sargent recognized this plant as a uniquely beautiful conifer and planted his specimen not on the grounds of the Arnold, but squarely in his own front yard in Brookline, Massachusetts.

A SENSATION

Nurseryman Samuel B. Parsons was so taken with the form of this hemlock that he took cuttings from Henry Sargent’s specimen and grafted these onto the straight species eastern hemlock. He grew these propagules at his nursery in Flushing. In 1876, Parsons & Sons took several of these specimens and exhibited them at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia “creating a sensation among horticulturists.” By 1879, Parsons & Sons was offering these plants for sale as “the most graceful and delicately beautiful evergreen known.”

Some of the highly vaunted plants exhibited at the Centennial Exposition ended up in gardens in the Philadelphia area, including two that were eventually planted at the estate of John and Lydia Morris. One was planted near the Swan Pond, and the other near the Key Fountain. The tree at the Swan Pond grew happily for over a century before succumbing this winter to the weight of a wet snowfall. The sister tree to this hemlock is still growing happily at the Arboretum. However, it is no longer near the Key Fountain. In 1947, this tree was moved from its “crowded quarters” at the foot of the Germantown slope to its new home at the Meadowbrook Avenue gate. The root ball of this tree weighed approximately five tons. Moving it required “ingenuity and patience” as the Arboretum staff at the time did not “possess equipment for handling large trees.” Yet somehow, they managed to move this behemoth a half mile uphill to its prominent position at the original estate entrance.

The weeping hemlock that General Howland discovered was never found again in the woods on Fishkill Mountain. It persists today thanks to the efforts of nurseries and gardens. And although the venerable weeping hemlock at the Swan Pond is gone, it will remain in the garden. Thanks to its natural resistance to decay, hemlock branches make an ideal choice for using as edging materials. Our once great hemlock will line the paths of our woodland trail to the Wetland.