Blog

#90YearsofMorris: Conservation of Philadelphia's Trees

In the late 1600s, when William Penn planned Philadelphia, he envisioned a "Greene Countrie Towne" replete with wide tree-lined streets, parks, and open space because he understood and embraced the value of trees in developing areas. Around 1700, this was further exemplified by Penn implementing the first ordinance in the colonies to protect Philadelphia’s public trees.

Subsequently, Philly prospered and grew, as did its trees. However, during the Industrial Revolution, many trees were removed, and the survivors suffered from the accompanying smoke and pollution. Citizens and the Fairmount Park Commission became deeply concerned that the impacts from industrial development were resulting in unhealthy trees and declining tree-related benefits. Rodney True’s speech below testifies to those concerns about how our urban trees were bombarded with a panoply of problems such as horses gnawing through tree bark, poor pruning practices, vehicle damage, pollution, and poor quality urban soils.

These problems persist to this day. In the mid-1970s, Philly had about 300,000 street trees, as noted in Tree Maintenance in Philadelphia by Robert McConnell. In the past 50 years, the declining budget of the Fairmount Park Commission, now the Philadelphia Department of Parks and Recreations (PPR), resulted in the loss of nearly 200,000 street trees, and today about 115,000 survive.

However, there is a renewed but timeless concern about managing and increasing Philadelphia’s tree canopy. PPR’s Philly Tree Plan is an excellent example to strategically address the problems that confront our urban trees. Additionally, Pennsylvania Horticultural Society's TreeTenders and other groups and organizations are partnering to improve tree care regionally. An apropos line from Ecclesiastes declares “…there is nothing new under the sun”—our urban trees continue to face many challenges, some old, some new, but it still takes a community to grow and care for a tree.

- Jason Lubar, Associate Director of Urban Forestry, Morris Arboretum & Gardens

Conservation of Trees

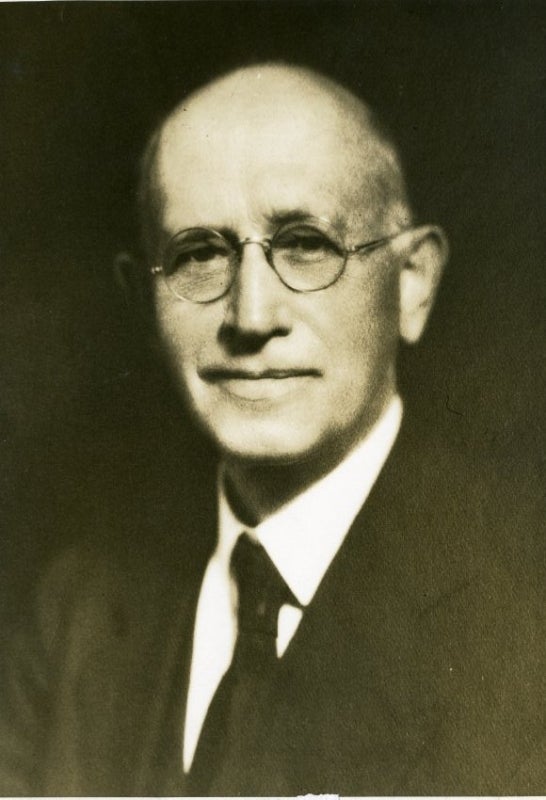

The below speech was delivered by Dr. Rodney H. True, first director of Morris Arboretum, on Wednesday, October 16, 1935, over radio station WFIL for the Council for Preservation of Natural Beauty in Pennsylvania.

People who live in cities sometimes have a hard time keeping in touch with Nature. They must leave home or go to the limited areas preserved as parks. An attempt to maintain a slender connection is seen in the trees planted along the streets.

I want to speak a word for those trees. They have a hard time of it, tough citizens though they must necessarily be. Their root systems are forced to grow under water-tight roofs of asphalt and concrete, and are forced into the presence of sewers, gas pipes, and other underground features that can give little help and occasionally much harm. Above ground, they are obliged to live in an atmosphere more or less man-tainted with coal smoke, industrial gases and particles of carbon that tend to block up the pores of their leaves, through which carbon dioxide escapes and oxygen enters. Sometimes, the insult becomes too much to bear and they languish and die.

The delivery horse, while waiting for the driver to leave his bottle of milk or loaf of bread, used to relieve the tedium by gnawing the bark of the street tree. The careless driver of the coal wagon still breaks or damages the lower branches of trees and lets fungi into the wounds, from which starting points the rest of the tree is invaded. As trees grow old, and larger, their bases push out nearer to the curb and are often damaged by the hubs of wagons and cars that knock off areas of bark. These areas, again, let in fungi that bring delayed destruction.

Sometimes, trees suffer because of well-meant efforts of friends. Heavy iron tree guards are sometimes set up around trees to protect them from the horse and other danger. In time the tree fills the guard, and unless the friend relaxes the pressure by opening it or by removing it, the guard cuts into the tree, sometimes quite or almost ringing it.

But, the danger is not over if the roots do find a source of water and minerals down under the street and sidewalk. Even if no horse gnaws off a patch of bark and no wind tears off branches, even though the coal cart has been mindful and the trees make a fine, rapidly growing top, as they become taller another danger threatens them, and the better the growth, the greater is the danger. Some morning in late spring or summer, a gang of tree pruners comes into the street armed with saws and shears, and proceeds to cut the top off or take out part of it, leaving it a caricature of a tree, a misshapen, mangled thing, whose only offense was that it was in danger of reaching the wires. The street, after such a visitation, is a sad sight. The truck following the gang is full of tops and branches of trees that did too well. They are left with their untreated wounds inviting fungi to come, and after years of delay complete the ruin. It may not be known that an owner of trees has a right to forbid such operations.

So, we inconsistent humans, obeying a sane impulse to have shade and coolness and a bit of natural beauty, plant trees in cities. The trees struggle more or less successfully with bad root conditions and with man-made atmospheres, only in the end in many streets to suffer mangling from hasty gangs, who must keep the wires clear by the least troublesome and least expensive means. All cities do not do things this way, but one not far away does.

The city, having streets shaded in the summer by healthy trees, bordered in the fall with the gold and crimson of autumn, and beautiful in the winter with the stark but marvelous architecture of stems and bare branches, is a better place for us humans to live in than one lacking these things.